Remember playing when you were a kid? What a wonderful experience! You're free to poke at things and understand them on your own terms. Remember when you started school? If your education was like mine, I imagine it involved a lot of sitting on a desk and staying still while the teacher was pouring information into your mind. There must be more options between those ends of the spectrum, a way to learn new things without falling asleep...

1. Chop up the tutorial

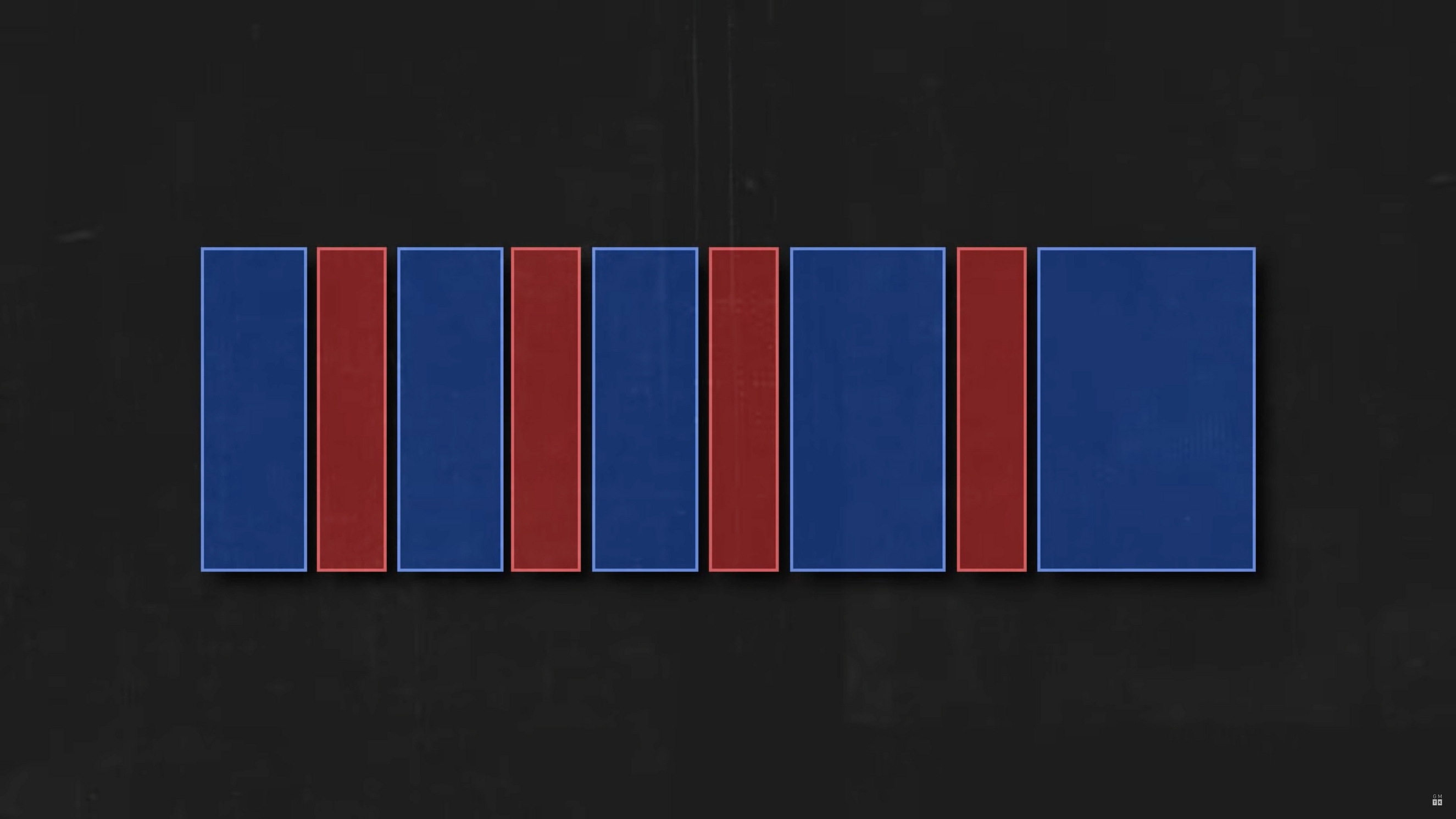

Let's say we sprinkle learning between the experience of playing. Imagine how these activities would look plotted over time, where blue is play and red is learning:

It's good to have both learning and play. Learning gives us new information, while play lets us experience it in different contexts and have fun. But, there's a quirk of the human condition we need to take into account.

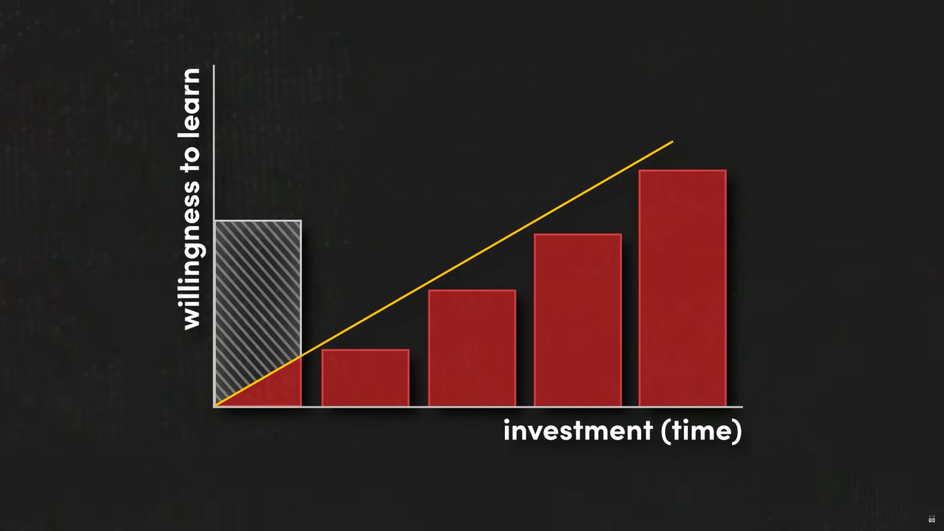

A person’s willingness to learn grows along with their level of investment.

Dumping a lot of information at the start is often wasteful because it exceeds people’s willingness to learn. If there is a small initial amount, you can jump straight into the action instead of having to go through something boring. In fact, if each step of the tutorial is small enough, it won’t feel like a tutorial at all. By delaying these tutorials, we can deliver messages when they are actually relevant.

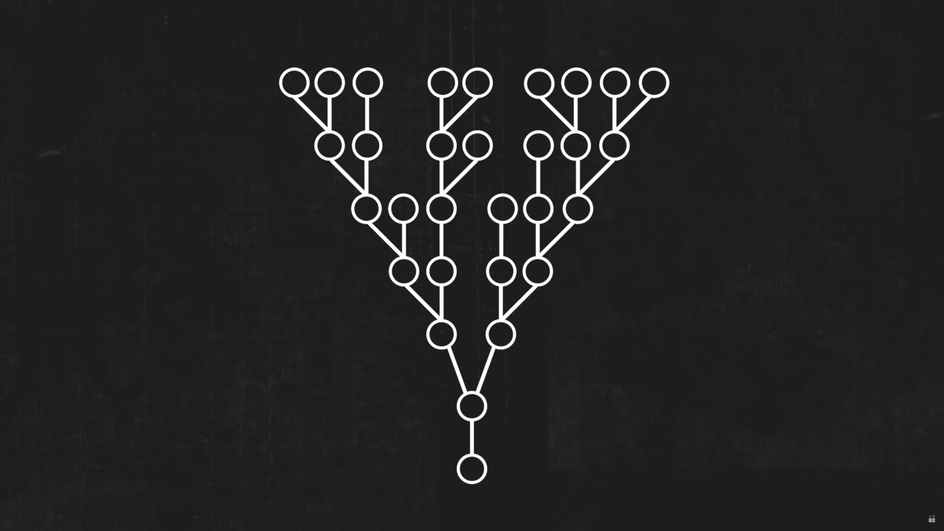

What if we have complex systems? Complex systems typically need to teach everything from the beginning, because every subsystem talks to each other, right? Let's say we're playing the game Civilization. A complex game. On your first turn, you need to make 1 decision:

Where should I settle my city?

And one decision on your next turn:

What should I build there?

By the time you realize it, you’re making dozens of decisions per turn, juggling all of the systems the game throws at you.

Civilization uses a technique called the inverted pyramid of decision making. A term coined by the game designer Bruce Shelley. This lets complexity grow organically.

What if we approach it a bit differently? Instead of peppering tutorials throughout an exercise, we can zoom out and put tutorials between entire chapters of play.

It's not easy to do, but it can be effective at pacing the teaching with respect to the learner’s investment.

2. Make learning fun

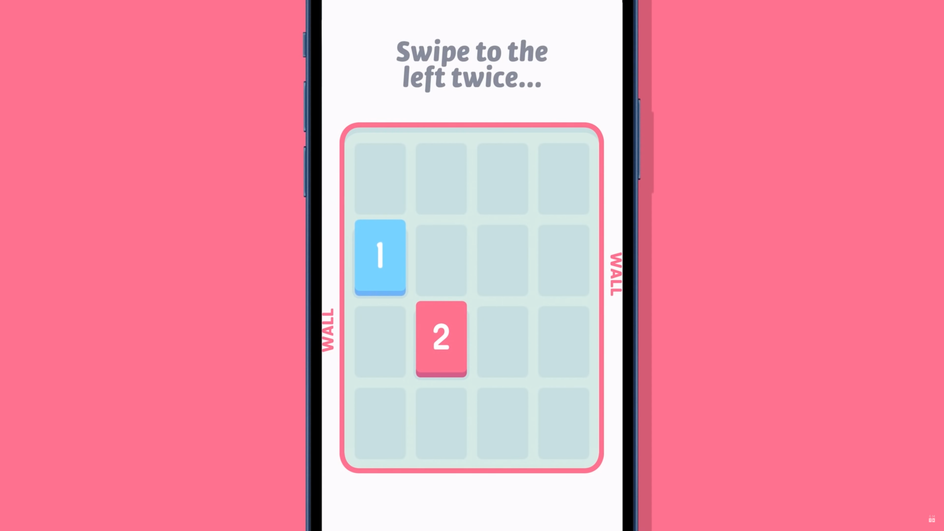

What if the system we’re teaching doesn’t accommodate that and we must front-load the tutorials? In that case, can we come up with a more effective and fun way of learning the basics? I can think of a time where I had to follow a tutorial and it tells me where to click step by step.

As far as the game is concerned, I have advanced. But as far as my brain is concerned, I've learned nothing.

Asher Vollmer - designer on the game Threes, from the video "How to make great game tutorials" on GDC Vault.

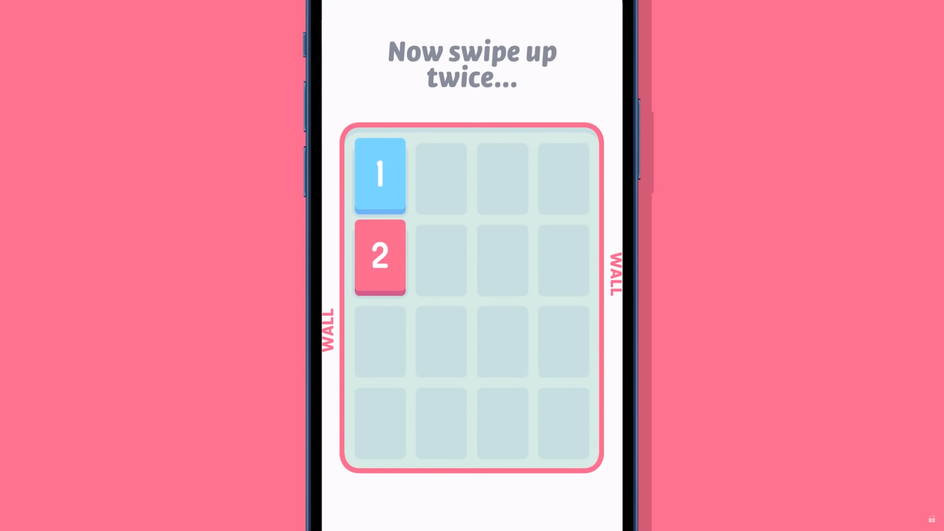

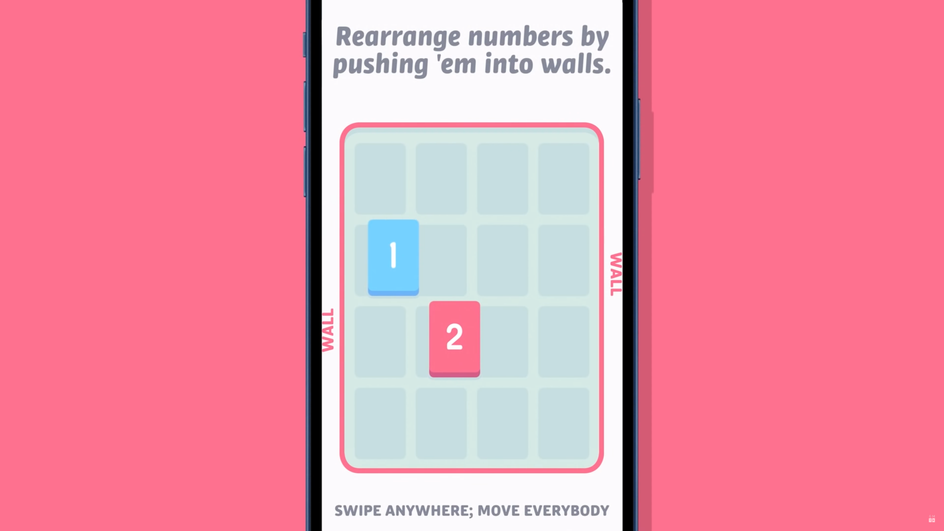

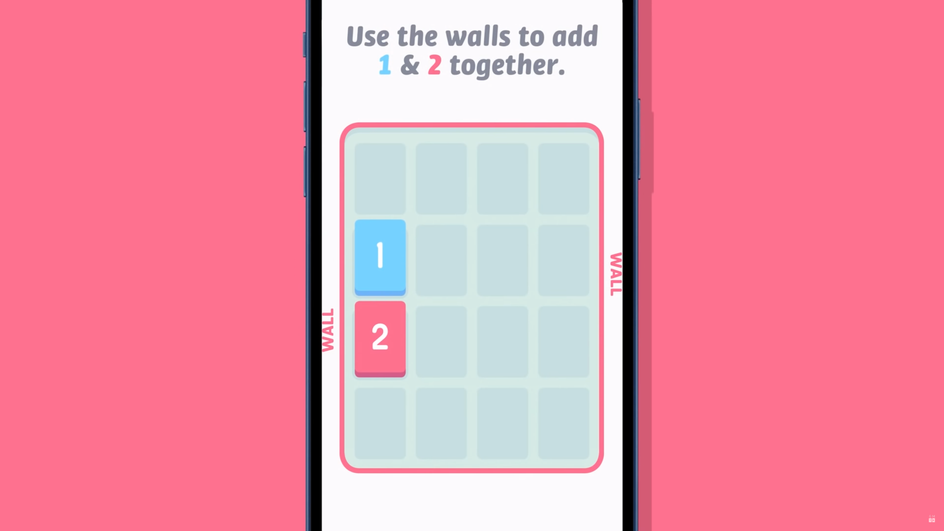

Blindly following instructions isn’t an effective way to learn. If you were teaching this puzzle game to people, you could ask these things:

Instead, the game designer decided to turn the instructions into a series of small puzzles for you to figure out.

This is a great way to add agency while still conveying the necessary information.

3. Shorten the feedback loop

The more opportunities you have to check how you did, the faster you will be able to learn. It’s easy to teach people how to do things, but it’s harder to explain why to do them. Speeding up the feedback cycle allows people to see the consequences of their choices for themselves and some advice along the way can offer recommendations and warnings.

4. Use affordances

Leveraging things that people are already familiar with can make it easier to learn new concepts. You know, spikes hurt, ice is slippery, coins let you buy things, keys open locks, let age = 5 assigns a variable. By leaning on things people already know, sometimes you wont even need a tutorial.

Summary

- Break each thing you want to teach into a list of minimum required knowledge and prioritize them.

- Break up the tutorial across an exercise or multiple exercises.

- Get the system into people’s hands so that they learn by doing rather than reading.

- Speeding up the feedback cycle allows people to see the consequences of their choices for themselves and some advice along the way can offer recommendations and warnings.

- Be intuitive, familiar and welcoming.

- Get people through the learning experience without them falling asleep.

I hope this was useful to you. This article is based on a video by Mark Brown from Game Maker's Toolkit. I'll leave you with a quote of his:

Teaching new people how to play is the only way for a franchise to grow its user base and avoid withering into irrelevance.

References

- Can we improve tutorials for complex games? by Mark Brown

- Introduction - the Rust programming language (example of a good mix of exercises and tutorials in text form)